“I was the first person to bring in a Ro-Ro into Africa…” – Alhaji Asoma Banda.

Alhaji Dr. Asoma Banda is the undisputed doyen of African shipping. By the way he managed the acquisition of O T Africa Line (OTAL) in 1985 and subsequently sold it to the Bollore Group in the 1990s just before a crunch, he proved his mettle, made a lot of money and a reputation that is hard to put down. At the end of the day, he ate his cake and still has it, for he remains the chairman of OTAL. In addition, he has devoted much time to developing his intermodal logistics chain, the Antraks Group, which is active in road, air and sea haulage in his native Ghana and other African countries.

A man of many official roles, Alhaji Banda is the executive chairman, Antrak Air, executive chairman of Antrak Express Ltd; president, Ship Owners and Agents Association of Ghana; board chairman, Meridian Port Services Ltd; and board member of Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority, Ghana Maritime Authority and The Ghana Shippers’ Council. At 71, and with his clout, Dr Banda has joined the ranks of kingmakers in his country – he has been a member of the Ghana Executive Council since the past three administrations.

In this exclusive interview granted the author during an academic excursion, Dr Banda narrates his humble beginnings and his meteoric rise to prominence, which culminated in hobnobbing with sitting African presidents and the captains of global maritime industry. He joined some major European ship owners and fought against the conference system upon which many African carriers depended to pay their way at the time. As he admitted to the magazine, he became the black sheep to African shipping lines and fought until the conferences were abolished and many African carriers subsequently closed shop. For reasons best known to him, Dr Banda rejected the UNCTAD 40:40:20 code, an option that was set up to make it easy for developing countries. All said, he chose not to dine with the devil, perhaps from foresight. A few years down the line, it paid off: all his kinsmen in the trade died off, he alone was standing; bruised but still standing. Does he have regrets? What axe did he have to grind with African national carriers and the conference system? According to him, “If the chairman of Black Star Line was going to London, he would go with an entourage. In Liverpool, they would put him in a Rolls Royce, all these things they were paying but they didn’t know.”

In this piece, Dr Banda delivers an epilogue on Africans in the shipping trade. We have tried to adopt a faithful rendering of his account because of the historical relevance of the story. All lovers of Africa’s indigenous transportation industry and its history will find this nostalgic and insightful. Excerpts:

DDH: The genesis…?

Dr Banda: I started having interest [in transport because] my father had been in road transport. He brought me in and didn’t even allow me to further my education. Without training or anything, he brought me in to run it [the road transport].

DDH: What year was this?

Dr Banda: Just before [Ghana’s] independence, probably between 1953, 54, 55. So, I made a mess of it.

DDH: What level of education did you have at this time?

Dr Banda: Secondary school, O’level. I made a mess of it and he kicked me out. My mother is somebody who wouldn’t like a situation for me to hate my father because I was the only son, the only child of my mother with my father. He had other wives. My mother told me you have nowhere to go, stay with him. I could have come to Accra because I was a very staunch member of President Nkrumah’s party. And my father was in the opposite party, the party for people with influence. Even if you had one truck, you were a rich man, anybody who had a little money was a member [of the opposition] because Kwame Nkrumah was a verandah boy. And these ones were the first intellectuals, everybody followed them. So, automatically I went there. He kicked me out, my mother said I shouldn’t go anywhere. So, I stayed. I was going from one elderly person to the other elderly person to beg him for me. At the end, after 18 months, I went to see one chief but my father told him, ‘leave the boy alone; I know who he is and you cannot love my son more than me’. He told him that the former job he kicked him out of was gone for good. I had a private car, he took it away from me. So, I went to self-exile in Kumasi. Eventually he said I should come one morning and I went and met him sitting with his nephew. He said this man is going to travel. He said I should go to a town in present-day Mali, called Mopte, a very small town surrounded by water. So, I went. In those days, it was public transport, those open trucks, mammy wagons, you sit on long wood facing each other, in the sun, somebody that was driving a private car. (General laughter). To do what? You see, my father was in transport and dealing in cattle. So, he said I should go there with his nephew to go and buy cattle. I thought we were going to buy cattle, give them to shepherds and we come back. We stayed there for three months. Every other day, we would go to a nearby market and buy only one. Another day, we would go and buy two. That took us about three months to gather all the cattle, about forty-something or fifty. Then I asked if we were now going to return to Ghana? He said no, we are following the cattle. We are following what? He said yes. I said fine. I couldn’t even call my mother, no phone, nothing. I accepted it. It took us three months to come to Ghana on foot from Mopte. We came to the border of Ghana and had to stay there ten days for quarantine, for the veterinaries to find out whether the animals you are bringing are healthy enough to come to Ghana. It took us another ten days to come to the place where they will sell the cattle. They sold it. That’s sixty five days. In 1956, I went back again. Then I became very familiar with the town. I tried to make friends and spoke the local Fulani language. After the second time, he gave me £1,000.

DDH: Pounds sterling?

Dr Banda: Yes, the West African pounds then in use in Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Gambia. I took it and was able to buy a lot of cattle, brought it, sold it. So, now, it’s learning lesson. So, he bought me a Mercedes car. He wanted me to know the reality of life. But there’s nothing that would stop me following Kwame Nkrumah. After the independence, he [Banda’s father] was supplying food, where we lived in Kentampo, in the centre of Ghana, where the Europeans had made a recruiting centre. It was a little town controlled by two paramount chiefs. They gave the contract to my father to buy food for the army. Everybody knew him. And there was a teacher who came to the village to teach and struck friendship with my father. He persuaded my father to build two classrooms for the school. When they moved the recruiting centre to Kumasi, my father moved there and there was one regional minister at that time who, after my father had won a contract, cancelled it. I was very friendly with most of Nkrumah’s ministers and the state attorney. So, I told my father to sue the government. He said, eh! me; but I insisted. So, there was a young lawyer who came from London, they gave the case to him, prepared by people from the attorney general’s department. They wrote a letter for me to go and see the attorney general who was a white man. I pretended that I couldn’t speak English, so that I could have access to the man. When I reached there, and saw him, I started saying loudly, ‘Bature, Bature…’ [white man] despite people trying to stop me. So he took my letter and read it. After reading the letter, he said this cannot happen. He said I should go and come back but I refused. So, they brought an interpreter to explain to me…

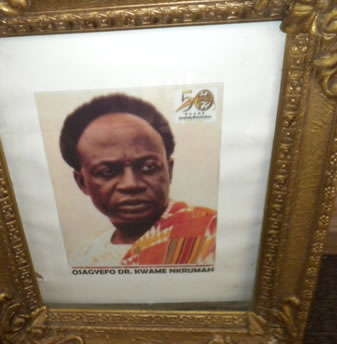

Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah.

DDH: Why the pretence that you couldn’t understand English?

Dr Banda: That was the only way I could get maximum attention of the attorney general, Mr. Jeffrey Bank, QC. He settled this matter, invited us to appear before cabinet, with my lawyer. Most of the ministers knew me because I was one of the staunch supporters… Nkrumah, as soon as he walked in, he said ‘that’s the young man, come’, with my lawyer. Then he invited the regional minister and said he should pay this compensation, surcharge the minister, and suspend him from Kumasi to Accra. ‘Any other thing on the agenda? he asked. ‘Young man, you can go.’

DDH: What was punitive about his move to Accra?

Dr Banda: He was the head in Kumasi as the governor but he was suspended and moved to Accra, to another job. So, our money was paid.

DDH: Your father was proud of that?

Dr Banda: Yes. Thereafter, Kwame Nkrumah called me and wanted to make me a district commissioner. I said no. He wanted to make me the regional organizer of the Young Pioneers. I said no, I didn’t want any government job. The request was coming from everywhere, so I decided to go to London to further my education, against the wish of my father. Because my father had this belief that if you go to London, you are going to be a Christian and you marry a white woman. So, I went and enrolled at a tutorial college at Tottenham Court Road.

DDH: What did you do there?

Dr Banda: I went to do my A-Levels. Then I told the professor that I wanted to read medicine. He said no, I didn’t have sciences. He said I should go and do law, I said no, my father won’t allow me to do law. Muslim to do law, to go and be lying in court? Then he said why don’t you do business? I said what business? He said you can do marketing. I said what is marketing? So, we were the first marketing students in Britain. There was no school, no institution, no textbook, nothing. Do you know where I went? Balham and Tooting College of Commerce.

DDH: To read marketing?

Dr Banda: Yes.

DDH: What year was this?

Dr Banda: 1964, 65. In those days, they wanted us to just gain more experience. So, if you do it for the first two years, they ask you to go to corporate bodies to work. You don’t get money, it’s part of your studies. So, I was pushed to go to British Overseas Airways Corporation, around 1963, 64. There, everybody liked me. It was a diploma course. When I finished, I was looking for a job. That time, it was just before Nkrumah was overthrown.

DDH: You were in London when he was overthrown?

Dr Banda: Yes, looking for a job. But one thing, Kwame Nkrumah was giving us a scholarship, £39 a month. Every Ghanaian student was getting it. The school fees for every Commonwealth student, be it university, college or polytechnic, was £39.

DDH: And he was paying you people another £39?

Dr Banda: Yes, as pocket money. Then he had Ghana Education Section attached to the Embassy. Then those first leaders, Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta, Nkomo, they bought a hostel in London at Maida Vale, called WASU for West African Students Union. So, I went there to stay.

DDH: Is it cheaper there or what?

Dr Banda: It’s cheaper, even if you don’t have money. I could go to Ghana Embassy, they had something called Hardship Grant. If you had a genuine case, they would pay your hostel fees. So, I couldn’t go to any other political party than to this government that was making these provisions. At WASU, there were Nigerians, Kenyans. So when I got my diploma, I was looking for a job. A politician came to open a company, I worked for him. It didn’t last.

DDH: A Ghanaian politician?

Dr Banda: Yes. I ended up working for a British company. Then most of my friends were Nigerians. [Yinka] Folawiyo was selling second-hand cars [buying in London and selling in Nigeria]. So, the job I was doing, I used to go Africa, Middle East, everywhere. That was the time of the congestion [at Lagos ports].

DDH: Was that 1975 congestion?

Dr Banda: What of the one when the oil [boom] came? That was when the oil was $7 a barrel. We worked for [Dr. Nnamdi] Azikiwe too. (Chuckles).

DDH: Under what auspices?

Dr Banda: Azikiwe was a father to everybody. His office was at Belgravia, I used to go there.

DDH: As a business venture or in the line of politics?

Dr Banda: No, for business, I worked for him. So, I used to go Nigeria and there was this congestion. Then I went to Saudi Arabia to work, staying at one hotel near the old port. Then I saw them doing roll-on roll-off [shipping], and I said this is something that can make money in Nigeria. But I don’t have the money [to go into it]. All the other ships were using cranes but this one you drive in and drive out, Ro-Ro. I bought the idea. There was one of my friends, an accountant by profession, to tell you how naïve I was, he was working with Lloyds, so I thought it was a shipping company. I rushed to him and said Bob, let’s make some business, we would make money. He advised me not to leave my job. But I explained to him. He asked me, have you got money? I said I had about £2,000. He said but this will cost millions. Then the bank manager that was looking after me when I was in school, Mr Mayer, I went to him too. But he advised me to stick with the job for which the company gave me a house since I didn’t have money.

DDH: What was the name of this company?

Dr Banda: It was part of Imperial Chemical Industries. Then I requested a letter of comfort from him because with that letter the ship owner will release the ship. He countered that if I failed to pay they will come after him and I answered that if I don’t pay, that means the ship hasn’t sailed. I assured him I was going to open the account with him, all the money would be with him and he will make the payment. He said it made sense and gave me the letter. I went and gave it to the ship owner. I called two friends to join me as partners though one declined. So, we started. That time Nigeria had about 30 ships.

DDH: If Nigeria had about 30 ships, that would make the year to be in the 1980s?

Dr Banda: No, you see Kwame Nkrumah started with about 25 ships when we didn’t have anything, with the first DC10 [aircraft]. Nkrumah led the way, so Nigerians also went in. 1974, 1975, Nigeria had about 30 ships, Ghana had about 25, Cameroon had 12, I can tell you all because I have been in this business for a very long time. Cote d’Ivoire had 12, Togo had…

DDH: Some of them may be chartered ships?

Dr Banda: No. That time you could get Export Credit Guarantee to buy all these things. Even Togo had two. Benin had one. Then they formed what was called ‘conference’. My ship, I was the first person to bring in a Ro-Ro into Africa.

DDH: Which port?

Dr Banda: Lagos, Apapa port. But there was no berthing area for it.

DDH: What year was this?

Dr Banda: 1975/76. The port congestion was there. The only place you could have berthed the ship was Bull-Nose. I know Nigeria very well, even to build Tin Can Island port, I had to help Chief Joe Nkpan to build that port.

DDH: You helped him?

Dr Banda: No, I gave him the idea. When I said they should build a container terminal he said they didn’t need a container terminal.

DDH: But who was Joe Nkpan, a minister or what?

Dr Banda: No, he was the assistant general manager, operations and marine, Nigerian Ports Authority. [Alhaji] Bamanga Tukur was the general manager. So, I brought this [Ro-Ro] ship to tell you how naïve I was, I just sailed the ship.

DDH: What was the cargo?

Dr Banda: That time they had started all the flyovers in Nigeria. And they couldn’t bring the equipment. So Julius Berger and all the contractors would pay any amount to get their equipment into Nigeria. The ship was carrying heavy equipment. And that time, no containers. So I hired trailers from London, put them in the ship and flew lorry drivers in from London to come and discharge the trucks. [General laughter] It was a risk worth taking. I brought lorry drivers from London to come and discharge because there was nobody in Nigeria who could do it at that time. When I came to Nigeria, I got stuck because of the congestion and because there was no suitable place for my ship. I went to see the harbor master, Abiodun, and told him I needed his help.

DDH: What was the name of your company at this time?

Dr Banda: Just the same organization…

DDH: Was it O T African Line by that time?

Dr Banda: No, I started with BFI. And this OTAL, I bought it from somebody. It was originally OT, that is Oil Tankers. They went bankrupt.

DDH: What year was that?

Dr Banda: Around 1985/86. We bought the company and added A L, Africa Line. They asked me to join the conference, I said no am an independent man. Anywhere I went, there was a fine. I would pay.

DDH: Who fined you?

Dr Banda: The Port Authorities would say you haven’t got the waiver, you carried cargo, you didn’t do this, bla bla bla. Then in my strategy, I started befriending heads of states. I told them am an African little boy, am not an outsider here. The first person who bought it was Houphuet Boigny. I will show you the watch he gave me. He made six of those watches, he gave me one. [President Gnassingbe] Eyadema was my best friend. I made sure all African leaders I penetrated them, because, you see Kwame Nkrumah wanted United States of Africa. Then they [the conference] formed UKWAL and the man running it was running Palm Line, Ken Birch. He asked me to join the conference, I said no. That’s why they pushed for 40:40:20.

DDH: Did you campaign for 40:40:20?

Dr Banda: I didn’t. I dismantled it. If you want to do something, read about it; 40:40:20 of the cargo they had gathered. Outside that cargo, you haven’t committed any crime.

DDH: This was your argument?

Dr Banda: Yes, my argument, I took it to Brussels [headquarters of the EU]. I said there was a monopoly going on here. So, they had to do it, five years of fight. That was the end, so they dismantled it. No more conference. And they fined them.

DDH: Were you happy about that?

Dr Banda: Yes, we were all instrumental to that. You see what they did was, that was what killed Nigerian National Shipping Line and Ghana Black Star Line.

DDH: But the removal of 40:40:20 also badly affected them…

Dr Banda: No, 40:40:20 means nothing. They killed African shipping lines. UKWAL, for instance, is run by Ken Birch. He is also a ship owner. So he put all the shoddy cargo to African lines and put the best cargoes to European lines. And they started changing their equipment [new ships] which took only one oil. Ours took about two different oils. And so it was very expensive to run. So, they came here [Ghana] one day, there was a conference, I went to the conference and after the conference, he said ‘there is a gentleman here we all respect, but he is an outsider. He needs to leave the room’. So, I went to the podium and took the microphone and said, ‘Mr Ken Birch, to come to Ghana and call me, an outsider. You are the outsider’. So, I left. I became the black sheep in shipping. If the chairman of Black Star Line was going to London, he would go with an entourage. In Liverpool, they would put him in a Rolls Royce, all these things they [Black Star Line] were paying, but they didn’t know. They were surcharging their accounts, for everything. So, they will go, big conference, yes, Black Star Line, this is your income, this is your expenditure, you’ve lost this, projection for next quarter, this is your profit. They will give you money to go for shopping, and bla bla bla. That’s what killed Black Star Line, Nigerian National Shipping Line, Sitram…

DDH: And Sivomar?

Dr Banda: Sivomar was only one [ship]. Houphuet gave that one to his son in-law. He gave him the whole of the Mediterranean line conference, no shipping line could carry cargo to Ivory Coast from there except Sivomar, run by Zanzu Simplicite, a journalist from Benin. Very handsome, very nice.

DDH: So you met him too?

Dr Banda: Yes, I know Zanzu very well. There is nobody in shipping in Africa who doesn’t know me.

Dr Banda shaking the US President during his visit to Ghana.

DDH: And you know them all too?

Dr Banda: Everybody.

DDH: So you struggled on your own and clawed your way to the top?

Dr Banda: Yes. I became number three in West Africa, OTAL, after Bollore and Maersk Line. When I was in Nigeria, they were not liner operators, they were only car carriers.

DDH: Number three in what category, cargo carriage, ship ownership or what?

Dr Banda: Cargo carriage.

DDH: How many ships did OTAL have?

Dr Banda: About twelve ships.

DDH: When did OTAL go out of business and why?

Dr Banda: 1999. It’s a very interesting story. None of them liked me, I was like a black sheep.

DDH: That is the African shipping lines?

Dr Banda: No, they had already died by this time. Then they realized that what I was telling them about the conferences was the right thing. So, there was the sale of a company in South Africa, Safmarine. I offered to buy it $350m. Bollore offered $450m. Then from nowhere Maersk Line offered $800m. They bought it. Bollore used to be number one, so when they bought Safmarine, Maersk became number one. Me, my position is there, number three. Then Bollore devoted money to get his position back. And when two elephants are fighting, who suffers? The grass. But in business, there is no pride.

DDH: But who did he offer money to?

Dr Banda: He gave it to his boys to get his position back for him, reduce the prices, go for price war. That’s what happened [they cut the freight rates]. So, am the only one who was going to suffer. Why should I be proud? A little African man in shipping and nobody knows me in Europe? So, I went to him and said, Vincent, you are doing this for money, do you want my company or you want partnership? So, I offered to him. It took him three months to say yes I will do it. So, it was a very tricky stance that had to be taken because if I told my staff I was selling they would all resign and go, and there would be nothing for me to sell. The staff made the attraction.

DDH: So you went to him before it came to the crunch?

Dr Banda: No, I wouldn’t even wait for the crunch to come, there was no crunch.

DDH: You knew that if you hung on…

Dr Banda: Oh yes, I would lose my ten, twenty, thirty years in shipping business, so I swallowed my pride.

DDH: Did he give you a good price?

Dr Banda: Yes, of course. But it was me he wanted. So, when I pushed, he said ‘yes I will buy the company but I want you’. I said I am not for sale.

DDH: Why did he want you?

Dr Banda: Because, look, my name in the market is something. He said I should remain where I am.

DDH: As the chairman of OTAL?

Dr Banda: Chairman, everything, money, the allowances, my expenses.

DDH: And he still paid you for the company?

Dr Banda: Yes, he paid.

DDH: So, you pocketed the money and remained in the same position?

Dr Banda: I am still there. That’s what happened.

DDH: Thereafter, you went into airline logistics?

Dr Banda: Transport is my business, I cannot quit. I have road transport, I have airline. But I have vested interest in the Bollore outfit because I had a very good logistics company in the whole of Ghana, Antraks Logistics. I even have Antraks Australia, intermodal, because you can’t do oil if you have no affiliation in Australia, so we formed Antraks Australia.

DDH: How does it work?

Dr Banda: If somebody wants to set up an oil company, they give all the contract to me. I will put a ship in Perth, load it, come here, discharge and put it in the hatch for them.

DDH: Does it have to do with the fact that Ghana is now in crude oil business?

Dr Banda: Am in not in oil business. Oil can be a curse, oil can be a blessing. I can lift their equipment for them. The gas pipeline from Nigeria, I laid it from Benin Republic all the way to here.

DDH: The West African Gas Pipeline project?

Dr Banda: Yes. I do all the logistics. Gold [works] in Takoradi, we supply all the gold mines with limestone.

DDH: With respect to the shipping lines that failed, what do you say of government involvement in shipping?

Dr Banda: Government has no business in business. Create a middle class, let them make the money, tax them and offer services to the people. Now, my head office is in London, not here. So, now I have moved everything from London to Bahamas. I don’t know Bahamas. We were doing it before, Margaret Thatcher came, reduced taxes, we all came back. Now everybody has gone back again. High taxes only drive people away. In Ghana, in Nigeria, the government is the biggest employer. They don’t have business to do business.

DDH: How did it affect Black Star Line?

Dr Banda: That time I wasn’t interested, it was all political but when I came into shipping, I realized it was being done wrongly. The first chairman was a pharmacist, and he was putting his nephews and girlfriends. The same thing as in Nigeria, and Sitram and Camship, they were all run like this, politically. And the minister that they change very often in Africa is transport.

DDH: Why?

Dr Banda: It came to a point I made a pronouncement that Ghana and Nigeria and Cote d’Ivoire should start and the rest should follow, we need a maritime bank. And then these shipping lines should have been there, our seaports should have been developed with that money. Not to be run by Nigerians or Ghanaians, we have special people who run shipping banks. Maybe we should have produced ship owners in Africa. But no government in Africa will do it because that’s the only way they take free money. If the government needed money, they would say, call me the managing director of Nigerian Ports Authority, bring us N10m. So, there is lack of leadership.